Privacy, Policy, and Personal Data

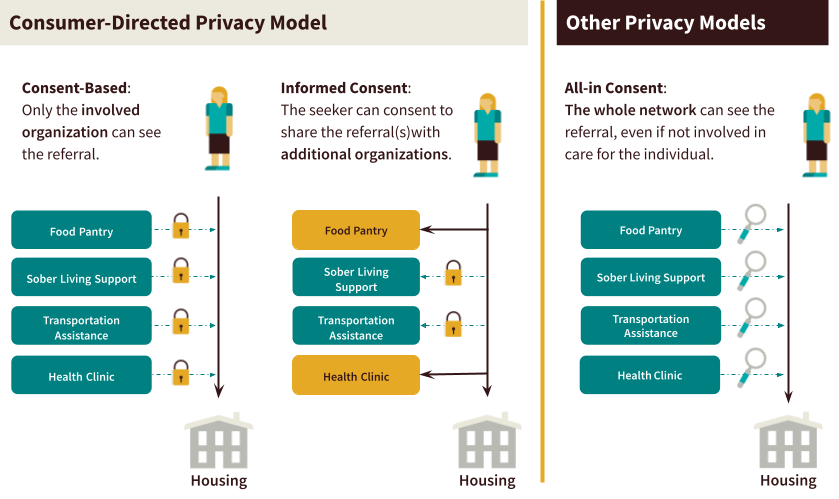

At Findhelp, we prioritize seeker privacy in all that we do. We believe in a consumer-directed privacy model, where individuals control who has access to their personal social care data through transparent, informed consent. Organizations should be able to access social care information based on care coordination responsibilities, and sensitive or private referrals should remain private with the seeker having the choice to share (or not). Data should not be sold for profit or shared at the whim of vendors.

We can strike a balance between enhanced care coordination and a trauma-informed approach to care while protecting the dignity and privacy of people’s most sensitive moments. It is a myth to suggest care coordination can only happen with a blanket (all-in) consent, especially in social care.

An Informed Consent Approach to Privacy

Some models, such as all-in consent, require blanket approval for someone’s personal information to be shared across a broad and undefined network, removing transparency from the person in need and increasing data leakage that may cause unnecessary harm.

Consider a person who shares with their doctor that they lost their job, cannot afford their insulin medication, and is facing some domestic partner challenges. Suppose the clinician makes some helpful referrals for free insulin and shelter support, but must collect a blanket consent from the person per the network vendor’s process. Suppose the vendor then shares (or sells) this information with risk stratification companies and allows hundreds of community organizations to search and access it, even without a direct referral or treatment relationship. There most certainly is a better way, and technology can help.

Findhelp’s Privacy Principles

In support of this consumer-directed model, we’ve adopted a transparent privacy policy that is publicly available on our website (company.findhelp.com/privacy/) and we adhere to the following principles:

- Transparent, Informed Consent

- Seekers know and consent to the full list of organizations that can see their information when they receive a referral.

- Seekers have the right to revoke their consent at any time.

- Permission-Based Access

- Organizations limit access to seeker information to only the staff roles involved in seeker care or operations.

- Seeker Access to Services with no quid pro quo

- Seekers should still be able to receive referrals or services without being forced to agree to broad data sharing.

Digitization of Social Care Information

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated awareness of and access to new technology focused on health and wellness. Usage of new apps, websites, and wearable technology skyrocketed, with millions of people in the United States taking advantage of this newfound convenience and accessibility as they sought care in a number of different areas of their lives.

Specific to telehealth and tele-therapy offerings, State legislatures acted quickly to ensure claims for new models of care delivery could be processed, and many niche startups in the telehealth space became mainstream. Industry leaders agree that healthcare required this innovation and policy attention to modernize how people receive care in their moments of need; however, there is often a dark side that accompanies progress. In this case, some companies are taking advantage of the people using these new services by inappropriately selling their personal data.

The Sale of Personal Data

Joanne Kim, a researcher with the Duke Sanford Public Policy School, contributed to a report on data brokers and the sale of sensitive mental health data in the United States.

Highlights from the report

- 11 out of 37 contacted data brokers were willing and able to sell mental health data and health care records.

- 10 data brokers advertised highly sensitive mental health data on Americans, including those with depression, insomnia, and anxiety. The data also included ethnicity, age, gender, ZIP Code, religion, children in the home, marital status, net worth, credit score, data of birth, and single parent status.

- A specific data broker went as far as to offer names and postal addresses of individuals including those with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), personality disorders, and strokes, and included their race and ethnicity.

- Pricing for this information varied: some offered licensing models of $75-$100k, while others charged only hundreds of dollars for 5,000 records.

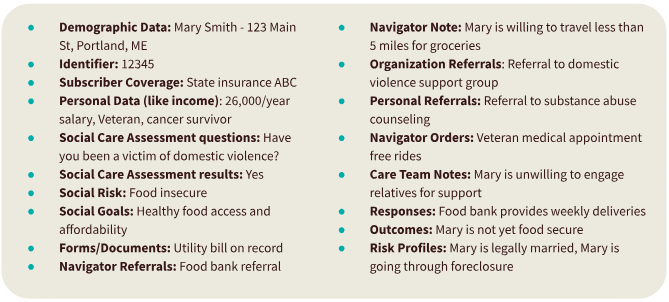

For illustrative purposes, below is a subset of the data that is typically collected when helping a person address their social needs:

We can do better

There are vendors operating in social care today that oppose policies that restrict the sale of this sensitive data. In fact, one vendor is actively promoting the fact that they are a “solution for consumer insights at scale, along with individual-level SDoH scoring and monitoring for every adult in the United States.”

Personal data is already being sold to help the risk stratification companies make a profit off of our most sensitive information.

Consumers, policymakers, and the industries that serve health and wellness need to pay attention to the implication of personal health data being sold for a profit without consent. We must improve consumer protection across all sectors that serve the health of Americans; we cannot assume existing safeguards will prevent the violation of private information.

This is an unacceptable gap in privacy and consent, and we must and can do better with policy and consumer transparency. Vendors shouldn’t be choosing the rules of privacy; consumers should be in control.

Community organizations agree

Watch community organizations share their support for an informed consent approach to privacy.

Legislation and Advocacy We Support

We are pleased to see NH Senate Bill 423 recognize these gaps in privacy and act to protect New Hampshire constituents. We’re also pleased to support Assemblymember Weber in California, who is championing CA Assembly Bill 1011 to prevent the sale of private data.

We support and will help champion these and future efforts to close the privacy gap in the social care space, to ensure that constituents have transparency, control, and continued dignity in their journey to a better quality of life for themselves and their families.

Dive Deeper: Our Privacy Editorial

Privacy policy and legislation is a complex issue, with inconsistent or contradictory components state-to-state. You can take a deeper dive into the social care implications in our new editorial, “Consumer Privacy and Consent: Implications for Social Care and Social Drivers of Health in the United States” written by our Chief Operating Officer, Jaffer Traish.