Our Pricing Policy: We’re Citizens First

On August 8th, 2006 I started my first day of work at MAXIMUS, Inc., a leading consulting firm focused on “Helping Government Serve the People.” I was there to support the firm’s efforts to deliver on Texas Health and Human Services Executive Commissioner Albert Hawkins’ vision to “make it easier for Texans to apply for services by modernizing technology and letting citizens choose how they want to submit an application — whether that’s in person or by phone, mail, fax or Internet.” I was 100% on board and excited to get started. Two years earlier, in 2004, I graduated from the LBJ School of Public Affairs and was ready to go “fix” the government. “Now’s my chance,” I thought to myself.

Privatization

Accenture was the prime contractor in this privatization effort and MAXIMUS was helping support their efforts. At the time, Accenture tended to hire the well-to-do children of well-to-do parents who were among the top of most of America’s elite universities. As a new employee on that project, I was struck by how professional — yet, how young — they all looked. I was also struck by how many of them there were. Turns out, an $840 million dollar contract will bring you lots of consultants at extremely high billing rates. They wrote about their award in a press release they published on June 30, 2005.

Not everybody looked at this contract with excitement. In the first few weeks of starting my new job I looked out the window and saw protesters from a local employees’ union marching around my building. They had concerns about how this contract was being managed. Their concerns were valid. I would later learn the contract was not being managed very well at all.

Things Fell Apart

For the first few months, I had a chance to work closely with the Integrated Eligibility team. Integrated Eligibility was a vision in which anyone in need in Texas could fill out one application for government benefits — without having to go and apply through several different departments. It was meant to make it easier for people to navigate the bureaucratic application process during their times of need. There were lots of meetings, big thinkers, and whiteboard sessions. I made it a point to stay quiet in meetings for an entire month so that I could learn as much as possible (and I didn’t want to sound like an idiot). In the first six months I also led a few projects, including a study of all of the eligibility rules involved in deciding which Texans gets Medicaid, SNAP, TANF or CHIP when they apply.

Then — seemingly out of nowhere — on March 13, 2007 I learned from a news article that the project I was working on was cancelled. I had no insider knowledge of this and was just as surprised as everybody sitting around me. Later that afternoon I was called into a conference room with a dozen or so of my colleagues and was told about the transition. The company I worked for would now be responsible for helping the State of Texas manage that transition, taking over the operations of the project. It was a meeting that I’ll never forget, and turned out to be a pivotal moment in my career.

Rebuilding

Remember those well-dressed young consultants? They were leaving and doing so quickly. Our company had to backfill a few of the key roles so I had an opportunity to recruit a team, including some of my colleagues from the LBJ School. Almost immediately, I was promoted to the Director of Reporting & Analysis for Eligibility Services (a new name for Integrated Eligibility) — where I managed a team of business analysts, programmers, and project managers. We got to work. The years from 2007 through 2010 feel like a blur — but I knew we were making a real difference. Our team was a utility team of sorts — a catch-all for interesting problems that others didn’t know what to do with.

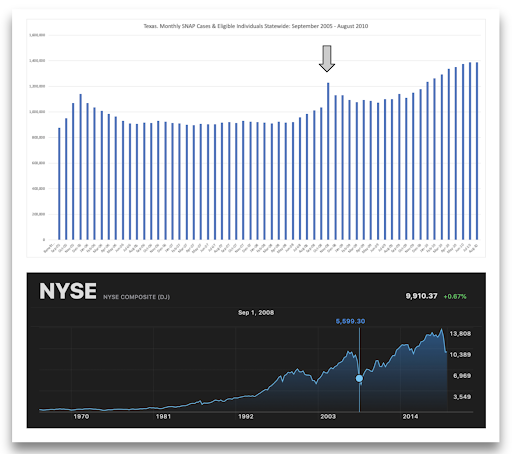

One of the problems we needed to solve was to forecast how many calls we might receive on any given month, day or even the time of day so that our company could appropriately staff the State Eligibility Call Center. When you call 211 in Texas you are presented with an option to connect to the State Eligibility Call Center. From there, an agent will help someone apply for services by phone. Operationalizing a growing call center isn’t always easy and it involves a deep understanding of: historical data, human nature (when people choose to make phone calls), and a little economic forecasting. For example, is there a relationship between the unemployment rate and the number of applications for public benefits? We had a hunch, but we would soon find out that — unequivocally, yes — there is a relationship.

Even Mother Nature seemed to have concerns about privatization. In early September of 2008 Hurricane Ike came along. With its devastation brought more and more people applying for government services — many for the first time. The State was inundated with new applicants for benefits and we could barely keep up with the demand to process those applications. Through a lot of overtime and some good public policy decisions like emergency SNAP payments — we helped a lot of people going through a rough time. I was proud of my team, I was proud of my company and I was proud to be a Texan. However, what we would face just a few short weeks after Hurricane Ike would surpass just about everything we would have expected.

The 2008 Financial Crisis

In September 2008, the global financial crisis happened. The stock market crashed. We went into recession. And month by month after this happened, we saw a dramatic increase in the number of applications for public benefits, including the SNAP program. Our company was responsible for taking these calls from people in one of their most vulnerable moments of their lives.

Most new applicants had no experience navigating public benefits, and many were in desperate situations. In my role, I often would dive into projects and analyze problems and fix things. I remember one night I had a chance to listen to calls that were recorded. I could hear the desperation in people’s voices and I could hear the call center agents being as empathetic as they could be. But that empathy wasn’t enough. In the image below, you will see a dramatic spike in the number of people enrolled in the SNAP program in Texas in December of 2008. This graph doesn’t fully tell the story of what was going on behind the scenes.

A Perfect Storm of Greed, Incompetence & Hard Work

Most of us heard the story of what caused the financial crisis. If you don’t remember, renting The Big Short will get you up to speed and it will get you angry. I just watched the trailer and I encourage you to do the same.

In 2008 when the American economy fell apart, a team of 2,500 of us were doing everything we possibly could to keep up with the demand for public benefits as a result. Thousands and thousands of people were newly dependent on the government for food, health insurance and money.

During those years I worked closely with the Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) group responsible for building the software that state employees used to process people’s benefits. Many were good people doing their best, but I also had the opportunity to see the underbelly of how government technology contracts are awarded, staffed and managed. And it made me sick to my stomach.

The Enterprise Architecture (EA) Team

The Enterprise Architecture team at HHSC was responsible for all of the technology infrastructure for one of the largest bureaucracies in the United States. Governments depend on their technology. Because technology can be complicated by eligibility rules and governance structures, good oversight of these contractors requires a deep understanding of the details. If that understanding isn’t there, sometimes people just take the contractors at their word when it comes to cost estimates and oversight.

Large consulting firms were hired to deliver technology. They would bill the State rates of sometimes hundreds of dollars per hour. Once these firms obtained these contracts, they would hire subcontractors. And sometimes, those subcontractors would hire subcontractors. And sometimes those subcontractors would hire more subcontractors — this is not an exaggeration. There were hundreds of these programmers on various projects around the agency. If the contracted rate for a software developer on a contract was $225 per hour, let’s say, that means the State was paying $468,000 per year for that software developer. If you asked one of those software developers who were actually doing the work how much they made, it was a fraction of the amount. In some cases, almost three quarters of what the state was paying was going to “pigs at the trough,” the many layers of firms taking their cut.

Many people knew what was going on. What struck me about these, and other issues, was that everyone just seemed to accept that that’s just the way things were. I believe that business could be a great innovator when partnered with government agencies — but weren’t we citizens first?

Judgment Day

While I worked on that project I spent a lot of time being angry. I was angry about how much money was spent on technology. I was angry at how much money was being wasted. I’m not against privatization. If done well, it really is the best of both worlds. But if governments don’t pay attention, businesses will take advantage. One hopes this corruption gets exposed, but for a while it didn’t seem like that would ever happen.

In 2012, the Texas Health and Human Services Commission entered into a sole source agreement with an organization called 21CT. This project blew up in a controversy that exposed much of the problems with the technology contracting process at HHSC. It took a while — too long for my liking — but eventually, sunlight exposed the corruption.

History repeats itself, it seems. Nine years later, governments are now showing interest in social care networks like ours. Some governments are putting out competitive RFPs to find a vendor. And some are not, choosing to take a sole source approach costing millions of dollars more than an equivalently sized state. At least one vendor in our space is telling governments that they are the only vendor that can do this work. They are not telling the truth. KLAS, a leading analyst, recently assessed five different solutions that do this work, and that report can be found here. When there are five vendors of a service, that’s more than one “source.”

During normal circumstances, governments go through a competitive Request for Proposal (RFP) process when they buy software and services. There are rules and best practices to prevent bad behavior by contractors and state officials. But we are not living in normal circumstances. With the influx of CARES Act funds — meant for emergency services like food, rent assistance and other vital goods meant to help — many technology vendors see dollar signs. Now that the trough is full again, here come the pigs.

Our Pricing Philosophy

I’ve learned a lot over the last 10 years about how companies are founded, funded and sustained. And sometimes I find myself with the same sickening feelings that I had 15 years ago. There’s a revolving door between the government and the venture capital industry. One day you help set policy for a $1 trillion dollar agency, the next day you’re a venture capitalist? Yeah, OK.

Newsflash, the system is broken and shortcuts are taken. Many of us are trying to answer the question of what we can do to change that. Lately I’ve been feeling more optimistic. We’ve witnessed the democratization of software with the Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) model. Companies began to offer software at a reasonable cost with unlimited users — without crossing ethical boundaries about creepy uses of data (like universal consents). There is something to be said for quietly striving toward what’s right and what the world should look like. In the spirit of that, here’s what we commit to.

Transparent Pricing

When we buy something, we’re used to seeing price tags. Whether it’s a t-shirt from the GAP, or subscribing to Netflix. We have become accustomed to easily finding out how much something costs. Some software companies do not publish their pricing — why not? Well, either they want you to sign up for a demo or they aren’t being consistent with their pricing.

We made a commitment to publish our pricing on our website in 2017. I believe price transparency is an important principle and it’s one of the reasons why more health plans, hospital systems, and other customers have chosen our product over our competitors.

Reasonable Pricing

We’ll always provide findhelp.org, the largest social care network in the United States, for free to everybody. For organizations that hire large groups of social workers, we offer advanced features they can subscribe to. We offer three subscription models for organizations — depending on what they need. Our customers can upgrade or downgrade at any time.

Commitment to Good Government

Despite the procurement problems I’ve seen in government lately, and despite the bad actors that are out there, I can’t help but feel optimistic about the future of IT in government. Things are moving in the right direction — just a bit more slowly than in other sectors. Organizations like Code for America and the US Digital Service have moved the needle on what’s possible and we continue to be inspired by their advocacy. To our current and future government customers, I can promise we’ll be fiercely protective of the trust you put in us. We’ll be straight with you and we’ll be good stewards of your investment.

I’ll close with a quick story.

In the fall of 2018, I had a discussion with someone in the IT Department of a major health system. I told him about some of these principles and shared why we believe in these things. I told him I didn’t like the way Healthcare IT worked — and that things should be different. And I told him by pricing the way we did, we were trying to change the status quo. He gave me a polite “good luck with that” and we parted ways. He may have thought I was a bit naive. Probably, but I don’t really care.

After all, we’re citizens first.